The MTU Trap – Challenging Value-Based SaaS Pricing

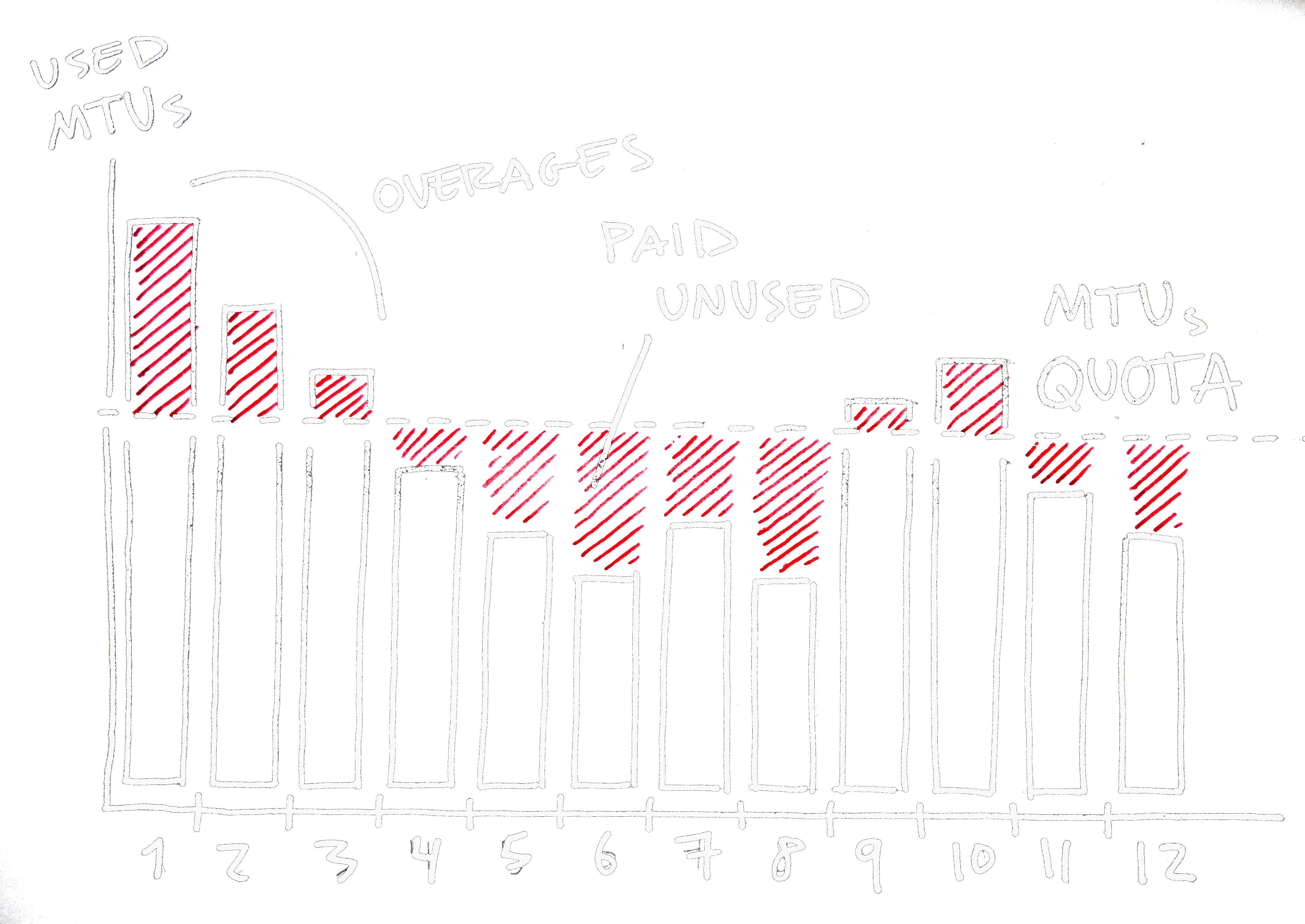

A deep dive into how some value-based SaaS pricing models can trick us and how to avoid them. The Conjurer, a 1505 painting by Hieronymus Bosch, depicts how a well-staged performance can distract us, while the real cost quietly slips from our pockets, and will help us to illustrate the MTU pricing model.

Many SaaS vendors in analytics, personalization, and customer engagement use Monthly Tracked Users (MTUs) as a billing metric. Think Segment, Amplitude, Heap, Mixpanel, just to name a few. The pitch is simple: pay for what you use, and only pay more as you grow. It’s marketed as fair, transparent, and value-based pricing.

But what if it’s precisely the opposite? What if MTU pricing punishes growth dynamics and charges for noise instead of value?

This post aims to:

- Unpack the myth of MTU pricing and how it might be working against you.

- Advice on how to unveil similar value-based pricing models that can become a liability and how to negotiate them.

How the MTU Trick is Played

1. The Illusion of Value-Based Pricing

True value-based pricing aligns cost with clear outcomes. For example, take payment and eCommerce platforms Stripe and Shopify. These take a percentage of your transactions: you only pay when value is delivered. Period. There may be some exceptions like refunds or returns, but the connection between cost and benefit is crystal clear.

With MTUs? Not so much.

The value of a tracked user can vary wildly. Some users generate revenue, while others just cost (through customer support, infrastructure load, or simply through the pricing structure itself). MTU pricing assumes all users are equally valuable, which they’re not. And while MTU-based pricing might push companies to focus on “quality users,” in practice you can’t realistically filter out low-value users upfront. At least not more than you can turn away visitors to a physical retail store just by their outfits and likelihood to buy…

MTU pricing is just pricing based on activity, not on value. The result? You pay more for user noise than user impact.

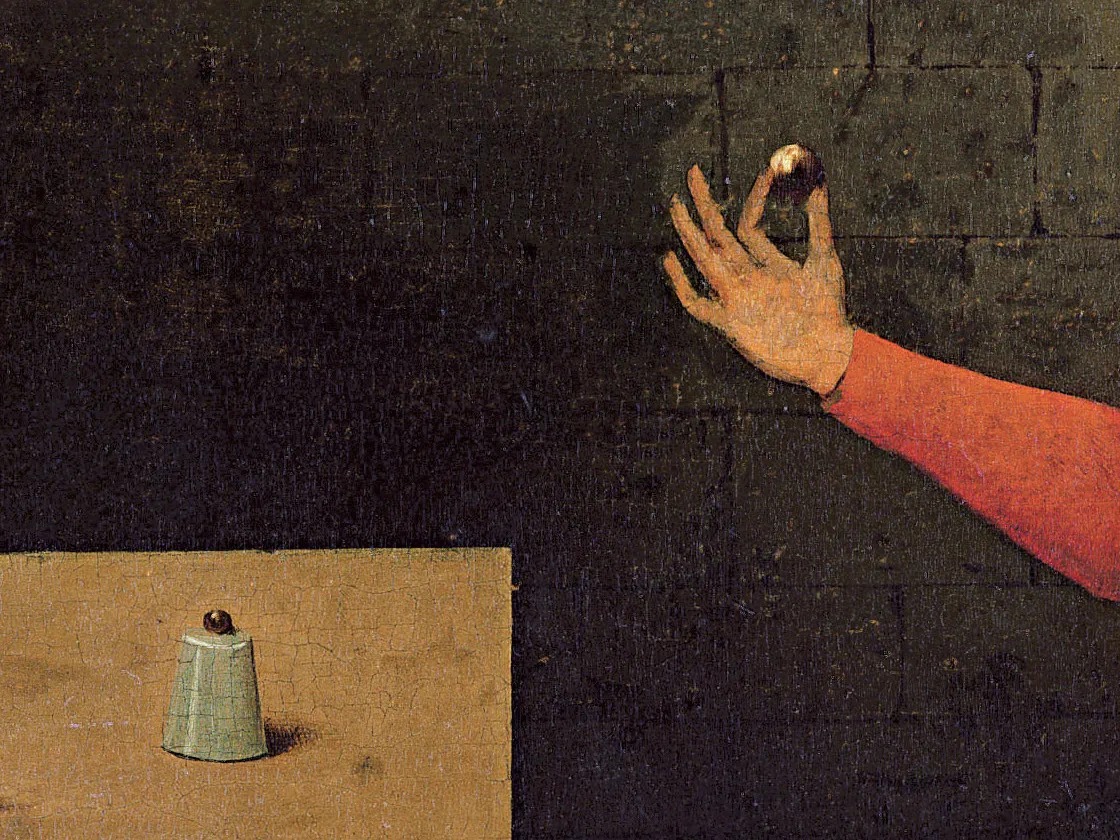

2. When Seasonality Becomes a Penalty

MTUs are usually sold on a flat quota. So, unless your user activity is flat all year round (which is rare, even if you sell subscriptions), MTU pricing punishes natural usage fluctuations.

Usage spikes? You pay overages. Lows? You still pay for what you didn’t use. Either way, the vendor wins.

Some vendors offer annual MTU allotments to smooth usage, but this only softens and masks the issue. With annual MTU allotments you still overpay if you use less and get penalized if you use more, just for the whole year.

The MTUs model rewards predictability and cash flow for the vendor, and punishes the customer’s seasonality.

3. Arbitrary Counts

Your MTU count resets monthly, your users don’t.

The way MTUs are counted (monthly, by default) introduces further disadvantages for most companies. User activity isn’t neatly segmented into calendar months, but quite the opposite. Many consumer purchase patterns revolve around paydays, which typically falls at the end or beginning of the month. A user who browses on the 30th and buys on the 2nd counts as two separate MTUs, potentially doubling your cost for a single real user.

While enterprise customers may negotiate more flexible billing windows, that’s the exception, not the norm.

The monthly user count frame is not just arbitrary, but skewed in favor of the vendor, not the customer.

4. Privacy, a Cost Multiplier

Modern privacy features, like Safari’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) and shorter cookie lifetimes, make it harder to recognize returning users. Result? You pay for the same person multiple times.

You can work around this partially, and some vendors offer sophisticated identity stitching to reduce duplication. But this often requires merging anonymous and identifiable data… something you can’t legally do under GDPR or other privacy laws without careful consent. So unless you have a robust consent framework and air-tight implementation, you’re paying for phantom users.

While your view of the customer becomes more fragmented, vendors profit off the mess without any additional cost from their side.

5. Hidden Costs, More Multipliers

MTU pricing rarely covers everything. Need to exclude bots? Add-on. Want to export your data? Premium tier. Need advanced governance or composability? Another product or plan.

Even if some features are flat fees, others add to the MTU price. This creates a compound billing effect, where adding features that makes the platform work effectively increases user cost.

To be fair, some platforms (like Heap) bundle more features into base plans. But across the board, costs add up fast as you grow and hit walls that require additional components.

What looks like simple pricing is just a gateway to a complex, always expanding renewal price tag.

6. Opaque Pricing, the Final Boss

And here’s the final kicker: MTU-based pricing is often not publicly available.

Segment, Amplitude, Heap, and Mixpanel don’t list prices on their sites. Instead, you negotiate with sales, who marinates the price between what you are capable of paying and the needs of their yearly growth targets.

Opaque Pricing is the final boss you can’t beat… Even if you manage to negotiate a good discount, your overage charges or feature prices will be quietly adjusted to offset the discounts given.

Avoiding Value-Based Pricing Traps

If you’re evaluating, or renegotiating a SaaS tool that uses MTU-based billing, or any value-based model, here’s what to watch out for and what to do:

| Red Flags | What to Ask or Do Instead |

|---|---|

| 🚩 No public pricing | Ask for pricing transparency upfront, including overages, contract renewal terms, and feature gating. Push for transparency or walk. Consider competitors that offer usage-based or flat-rate alternatives with public pricing. |

| 🚩 Pricing on vague metrics | Prefer event or volume-based pricing, when possible. Alternatively, push for metrics tied to business outcomes (e.g., revenue, conversions). |

| 🚩 Gated service essentials like GDPR and security compliance, governance or data exportability | Make sure you really know what you need, and what’s included vs. gated. Audit total cost of ownership: Include add-ons, integrations, and engineering time. Negotiate for bundled plans. |

| 🚩 No rollover on monthly usage you pay overages and can’t accumulate unused | Ask for rollover else quarterly or annual usage smoothing. |

| 🚩 Sales-controlled discounts with no standard logic for scaling | Request quotes for several growth scenarios. Benchmark pricing with peers or industry communities and don’t be afraid to walk! |

Conclusion: Pricing Should’t Smell

As a rule of thumb, if pricing smells off, it probably is.

If the pricing model feels unpredictable, opaque, or is not air-tight aligned with your outcomes: Walk away or try to crack it’s code to find out if it’s worth your while..

Value-based pricing is often appealing as a win-win deal, and that’s precisely why there is more reason to scrutinize how “value” is actually being defined and charged.

This “code cracking”, or “scrutinizing”, that I casually refer to, is something very well studied in Economics, specially by the economist Oliver Williamson, who would refer to them as Transaction Costs. These are the hidden expenses of using a market instead of owning or building the solution yourself.

Value-based pricing often thrives on exactly the kinds of friction Transaction Cost Economics warns about:

- information asymmetry,

- asset specificity,

- and vendor opportunism.

The more dependent you become, the more leverage shifts away from you and towards a pricing model that quietly compounds in complexity.

This doesn’t mean the value-based pricing is always a trap, far from it! If you scrutinize the value-based pricing of SaaS vendors, you’ll be happily surprised to find that some (not many) are playing the value-based pricing game fairly: Take Stripe (Payments), Shopify (eCommerce) or PostHog (Product Analytics) as some reference examples.

The key is to always scrutinize the deal, not being afraid to ask difficult questions to the vendors, and if still unclear, daring to walk away.