Data Teams: The Corporate Speleologists

This post is a tribute to Data Teams and Speleologists. A reflection around the unique combinations of culture, versatility and resilience needed to navigate organizational and physical depths, shed light on blind spots and endure many kinds of human and technical challenges for the sake of knowledge. The post is inspired in the discovery of the deepest cave on Earth: The Krubera-Voronya Cave, and the teams involved in the discovery. The cover picture shows the descent to the cave by Gergely Ambrus.

In the bowels of the earth. A flat-out 130m crawl at Krubera-Voronya. Bernard Tourte by Garcia-Dils.

In the bowels of the earth. A flat-out 130m crawl at Krubera-Voronya. Bernard Tourte by Garcia-Dils.

I recently came across the story of Sergio García-Dils and his caving team, who, alongside several other speleologist groups, have surveyed the deepest known cave on Earth: the Krubera-Voronya Cave. After years of excruciatingly meticulous teamwork, explorers have reached a depth of 2,144 meters, though the true bottom may still lie deeper!

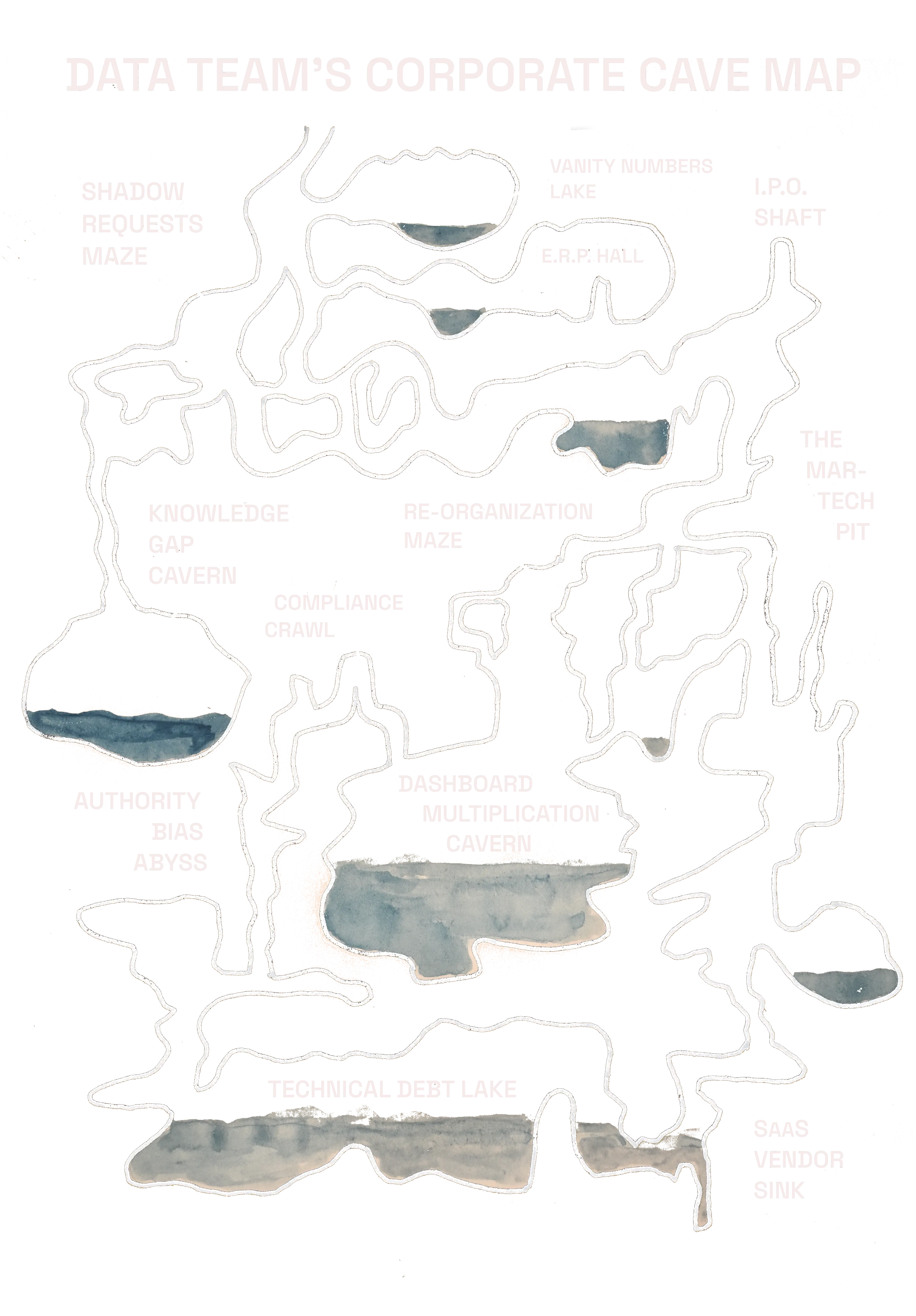

Everything about this discovery and the people involved is fascinating and a bit counterintuitive. While reading about the caving expeditions, I couldn’t stop thinking about the parallels between these cave explorers and data teams; their journeys into the dark and wet depths of the company’s subterranean cave system, beyond organizational charts and architectural diagrams…

And I began to realize that:

The comparison between data teams and speleologists isn’t just metaphorical. The parallels run deeper into the very structure, talent, and mindset of the teams who take on such endeavors.

A Rare Breed of Talent

Catch Sergio drilling an anchor in the deepest cave on Earth or exposing a Roman mosaic in Seville

Catch Sergio drilling an anchor in the deepest cave on Earth or exposing a Roman mosaic in Seville

Sergio García-Dils explains that in caving, everyone needs to do everything. The demands are brutally broad. Every team member must cook, climb, haul gear, map tunnels, dive flooded passages, read weather forecasts, or know first aid. Of course, some specialize, but survival and success in subterranean environments come from resilience and versatility.

There’s no formal school to become a speleologist. Sergio himself is an archaeologist and historian by training. The speleology trade is built through continuous learning, deep experience, and an unshakable drive to discover.

Character is so important in this trade that when building the team to explore Krubera-Voronya, the selection resulted in a group where the vast majority had grown up in families of speleologists, some even representing a third generation! Unintentionally, a team with extremely different backgrounds shared a culture and lifelong exposure to exploration.

The same is true for people in data. There is no formal education for it and many paths lead to the trade. You’ll find software engineers, economists, mathematicians, statisticians, business administrators, financial analysts, marketers, social scientists, or even journalists. And although some specialize in one area or another, data people are polymaths or hybrids by necessity: all need a certain fluency in data modeling, software engineering, statistics, change management, communication, product thinking, business strategy, and stakeholder management. On top of all that, they must develop a working knowledge of every domain they touch: finance, marketing, procurement, sales, product, logistics, and more.

Data work, like speleology, attracts people with strong curiosity, versatility, and a willingness to navigate the unknown. Both cave explorers and data teams thrive on persistence and adaptability when faced with challenges. And these challenges are as much technical as they are human and organizational.

If it Rains Outside, You Get Wet

Speleologist Maria Plotnikova at Krubera-Voronya Cave. Depth of 1340 meters.

Speleologist Maria Plotnikova at Krubera-Voronya Cave. Depth of 1340 meters.

It may not come as a surprise that speleologists don’t consider darkness a challenge. They thrive in darkness and even find the underground cozy, kind of like being inside the earth’s belly. They feel quite at home. And they have lamps! And the better the lamps become, the more they discover.

They aren’t afraid of uncharted territory or technical challenges; that’s precisely why they descend into the abyss. However, they are afraid of getting stuck, and getting wet.

In one of his interviews, Sergio Garcia-Dils comments that if it rains outside, you’ll get wet. A sudden change in weather can hit the team very hard, making life miserable for a while, or, in the worst case, putting it in danger.

Data Teams also thrive in darkness, in the realm of shadows and blind spots where business problems and opportunities hide, where there is unrealized value and competitive advantage to untap.

The realm of the data team is not the dashboard, the recommendation model, the ranking algorithm, the forecast, or the churn prediction. These are just by-products of what data teams do to gain knowledge or generate value. Underneath these, data teams deal with unclear definitions, debt from systems and processes, gaps in knowledge, and disconnected responsibilities and organizational schemas. They fill in the blanks, and bridge across silos.

And when it rains outside, data teams get wet, as well as the speleologists. And it’s not just about the old GIGO principle (Garbage In, Garbage Out), or a breaking change in a source system that requires fixing pipelines under a waterfall of stakeholder messages asking for updates on the incident resolution… some teams have past this stage.

When it rains, data teams get wet because they usually have central and overarching roles in the organization. When there’s a storm in any function, it will certainly hit them. When the finance department struggles with a new ERP implementation, when site conversion drops and everyone knows why but no one agrees on it, or when leadership needs to pull numbers for a due diligence (real quick), data teams are there to help. And they do it with pleasure! As long as they are not already hypothermic…

Like speleologists, data teams are used to operating in the darkness and getting wet, and they are technically and mentally equipped to deal with it.

Pulling Rank is Failure

Cave logistics at Krubera-Voronya. Credits to the Ukrainian speleologist Yuriy Kasyan

Cave logistics at Krubera-Voronya. Credits to the Ukrainian speleologist Yuriy Kasyan

In cave exploration, there is hierarchy, but it is rarely used to assert power. Sergio García-Dils is clear on this: if someone needs to “pull rank,” something has gone wrong. In the cave, leadership is not about titles but about trust, contribution, real-time decision-making, and rationality. Expertise flows fluidly. The person who knows how to rig a vertical drop safely leads in that moment. The one with experience navigating siphons takes the front when diving through flooded tunnels.

The same holds true for data teams.

In truly functional teams, authority is distributed and situational. Data work is too broad, complex, interdependent, and fast-evolving to follow rigid chains of command. In addition, data teams support rational, evidence-based decision-making, and pulling rank often goes against this principle.

The analytics engineer who built and maintains the marketing mix model understands exactly how a small change in campaign tagging could mislead an entire quarter’s performance review, and is therefore a key role in avoiding this from happening, and participating in the process of making decisions based on the model’s insights.

This is the way to go. But when a stakeholder uses authority to push a KPI definition, against the rigorous recommendations of the data team due to lack of feasibility or meaningfulness, the message is clear: truth is negotiable and imposable, and optics take precedence over understanding.

In environments that tolerate Authority Bias, The Highest Paid Person’s Opinion (HIPPO) in corporate slang, you might be better off without a data team at all: it will save resources and headaches.

Just like in a cave, when the data team functions well, decisions are fluid, rooted in shared goals, rationality, and not positional power.

Knowledge is the Reward

Mallory leading a team up Everest’s North Col around 1924 and how the summit looks today

Mallory leading a team up Everest’s North Col around 1924 and how the summit looks today

George Mallory, a British pioneer of the first Everest expeditions, was once asked, “Why did you want to climb Mount Everest?” He replied: “Because it’s there.”

Mountains are obvious symbols of aspiration, beauty, and adventure. To such extent they are, that we have normalized the sight of hundreds of tourists waiting in line to reach the Everest’s summit, standing along frozen bodies and abandoned oxygen bottles just to say “I’ve done it!”.

Mallory, who perished in the Everest summit attempt, could have never imagined how the mountain looks like today…

The boom of AI, especially in the field of large language models (LLMs), and the rush by countries and companies to win the summit race no matter what, brings echoes of the space race or the conquest of the Himalayas. It’s a high-stakes environment where scientific inquiry and technology, blends into nationalism, power, and propaganda.

This is very unlikely to ever be the case for speleologists, or data teams. Can you imagine queues forming to reach the bottom of Krubera-Voronya just for a selfie?

The journey through shadows and depths is not an obvious aspirational symbol for the many. If you look beyond the hype, the domain of data driven decision making and automation is as ancient as the use of astronomy or the census for taxing, agriculture and labor planning. The census has had a tremendous impact in human history, from ancient empires to modern democracies. But obviously the census is no blockbuster material like the Colosseum, the Everest Summit or the surface of the Moon.

Not even AI will make data teams appealing to the masses.

AI is a blockbuster, it revolutionizes and empowers data teams, just as synthetic polymers revolutionized mountaineering and speleology in the form of ropes, clothing, and protective gear. But technology won’t make data a domain for the masses, simply because the domain is out of the spotlight by design.

In a world obsessed with visibility and instant impact, it’s easy to overlook the quiet depth of data work. But like the explorers of Earth’s inner caverns, the data teams journey is downward, not to be seen, but to see.

And data teams surface valuable knowledge that helps the rest of the organization find its way. That’s the reward! And to me, that quiet, relentless pursuit, done in the dark, with few to witness, like the journey into the Krubera-Voronya cave, is nothing short of heroic.

Krubera-Voronya - Game Over Chamber. Credits to Gergely Ambrus.

Krubera-Voronya - Game Over Chamber. Credits to Gergely Ambrus.

For the map lovers

❤️

❤️